Mixed Feelings

Lessons from the Multiracial Donor-Conceived Community

Growing up biracial in an all-Chinese American family, I often felt like an oddity. I wasn’t the only mixed kid in my world – I didn't know anyone else who was mixed like my twin brother and I. My parents had conceived us with the help of an anonymous white egg donor, and the arrangement meant no one would give me more information about my heritage than a guess of “probably Italian.” It wasn’t until adulthood that racial dysphoria and repressed curiosity finally drove me to seek out people like me: multiracial and donor-conceived.

My search led me to donor-conceived support forums, where I realized that I'd have to build the community I wanted. I invited every BIPOC and multiracial donor-conceived person I came across to a chat group, where we swapped stories. Soon, I got the opportunity to develop a virtual peer support group for BIPOC and multiracial donor-conceived adults through Donor Conceived Community, a national nonprofit dedicated to the wellbeing of donor conceived people (DCP). Over eight six-week groups (and counting!), our community has grown to include people who learned that they were donor-conceived as kids or adults; come from diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds; and belong to families of many types, including different-sex, same-sex, and single parents. Story after story has taught me that there are more of us out there than we know – and our numbers grow every year.

Of course, the fact that many DCP are multiracial is no surprise to BIPOC family-builders. Media reports and the rise of specialty services like Asian Egg Bank and Reproductive Village testify to the fact that, even as more people become parents through donor conception every year, the options for donors of color haven’t risen to match. In fact, a 2021 analysis of eight US sperm banks showed that non-Hispanic white men represented 70% of nearly 1,750 donors. Meanwhile, out of over 1,500 egg donors across thirteen egg banks, 43% were white, 16% multiracial, 8% Asian, 24% Hispanic, and 9% Black; just 1% or less were Alaska Native, Middle Eastern, or Pacific Islander.

As a result of this parent-donor race gap, many intended parents have to (or choose to) conceive through a donor of another race. As a result, our community of multiracial donor-conceived kids, teens, and adults is ever-expanding. Mixed America in general grew by 276% from 2010 to 2020; today, 1 in 10 Americans are multiracial.

Yet, while much has been written about intended parents who struggle to find same-race donors...

..there’s little out there about multiracial donor-conceived people ourselves. How have we built our identities in a world where non-identified donation was the norm? What do we have in common? And, most importantly, how can parents, professionals, and the industry support the children growing up after us?

Whether you’re a professional, intended or recipient parent, donor, donor conceived person, or ally, here are a few lessons from our community of multiracial adult DCP.

Love may not (always) “see color,” but the world does.

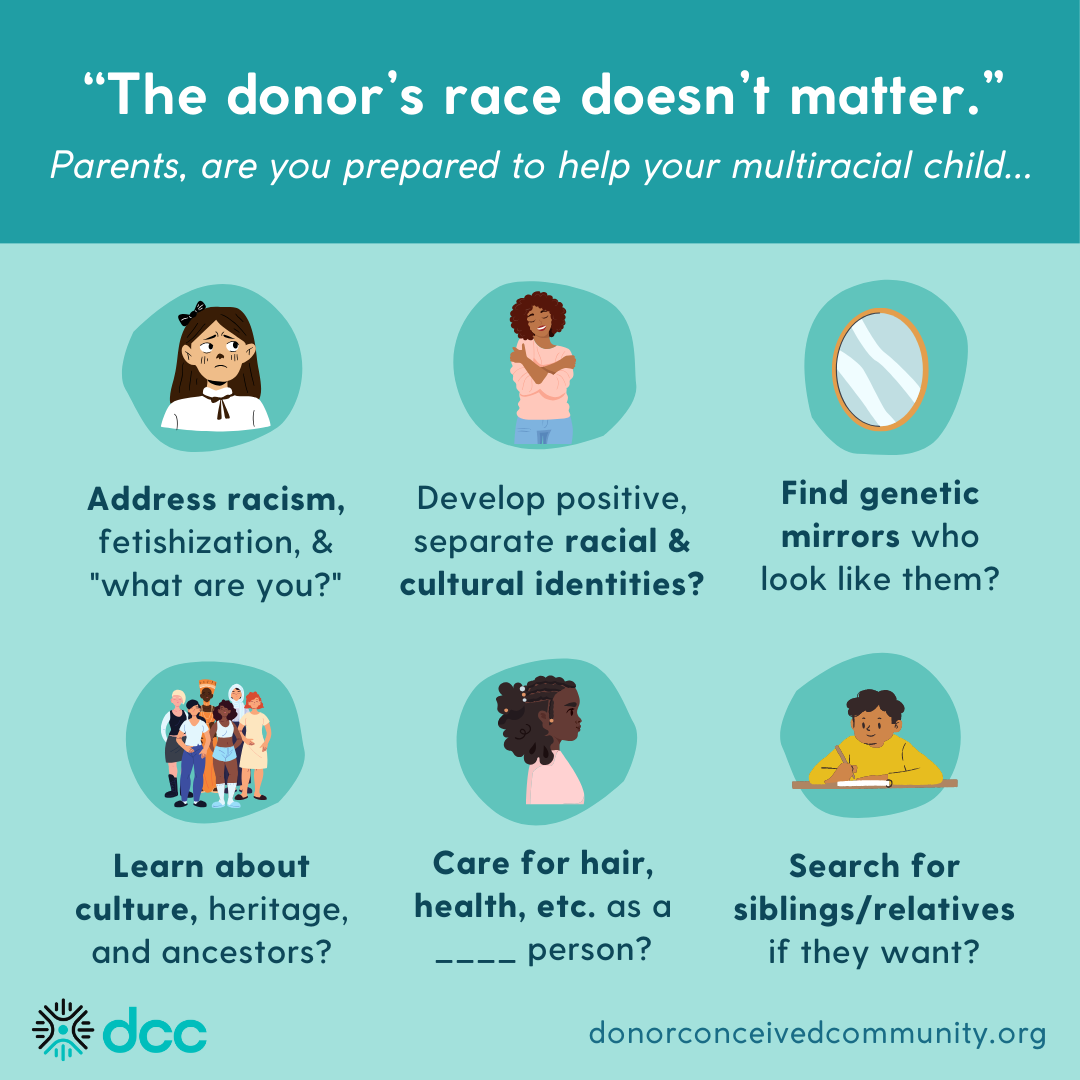

In the US, “colorblindness” has been touted as a solution to systemic racism for decades: Just stop talking about differences and discrimination will disappear. Family-building is not a stranger to this approach. In my work with intended parents and the professionals who support them, “I just want a healthy baby. I don’t care what they look like” is a common refrain.

Of course, reality is more complex. Studies show that, as early as ages 3-4, kids in the US learn from the world around them to associate pale skin and “white” features with being more intelligent, attractive, or trustworthy. It’s this world, not a colorblind one, that DCP grow up in.

Multiracial DCP often experience lifelong “signals” about race and ethnicity from family, community members, and strangers – even if we don't learn about our true heritage until adulthood. These everyday signals include comments about appearance (like "you're so much lighter than your siblings”), unsolicited questions (like "why don't you speak Spanish?"), subtle discrimination (like being cast in stereotypical acting roles), overt discrimination (like "go back where you came from"), and violence (like bullying, assaults, or hate crimes.)

One thing is clear: while the family-building field helped our parents conceive us, it did not equip them to help us navigate the rest of our multiracial lives, from racial stereotypes on dating apps to colorism in the media or racism in healthcare.

Access to donors, half-siblings, relatives, and heritage communities can help multiracial DCP develop fuller identities.

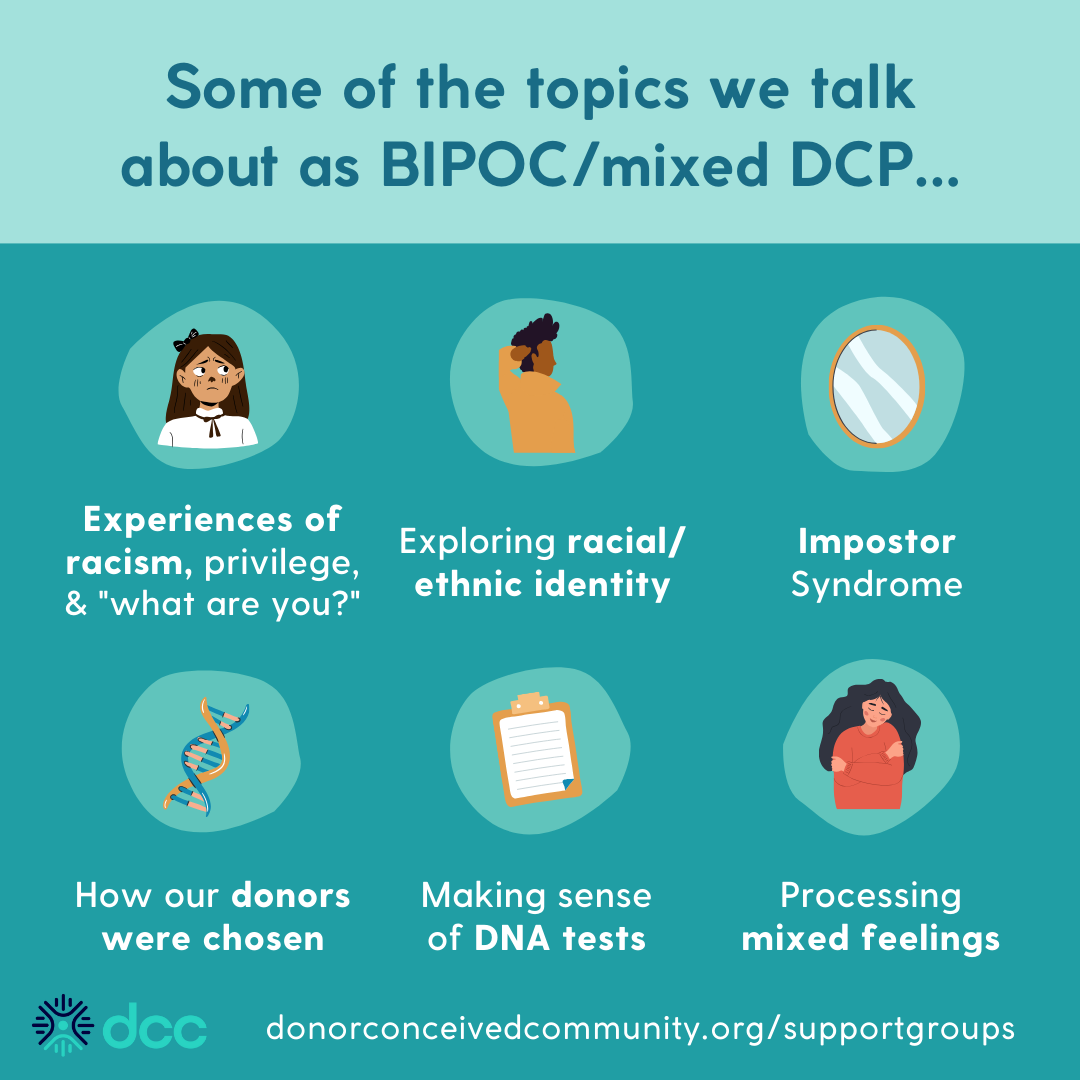

Racial, ethnic, and cultural identity development is another lifelong journey that many multiracial donor-conceived adults seek support for. Belonging and Impostor Syndrome are common topics in our peer support group. In fact, so many participants initially worried they weren’t BIPOC or multiracial “enough” to join that I started sending a reassuring FAQ to prospective members.

Why is this? Research shows that multiracial people start developing racial identities early on, working off the people we come from and the people around us. However, most of our parents chose donors who were anonymous or “Open ID at 18”, so we were raised without information about or contact with the donor or their family. It doesn’t help that many of our families received vague or inaccurate information about the donors’ heritage from banks and clinics. In some cases, this is a result of how flawed American racial categories are to begin with. For instance, the terms “Native American” and “Hispanic” may technically be accurate on a donor profile, but give parents and DCP little information. In some cases, banks, clinics, or donors have even misreported donor race and ethnicity, either by following standard procedures (like labeling Middle Eastern donors as “white”) or due to other factors and motives.

On the whole, our generation grew up disconnected from our racial, ethnic, and cultural communities, including “mirrors” like friends or role models. While many of us still strongly identify with the culture(s) we were raised in, donor anonymity makes identity complicated. If our families knew our full heritage, would they still accept us as Brazilian, Filipino, Cuban? If we explored our heritage or relationships with donor relatives, would we be disrespecting our loved ones? And what about our children – what can we pass on to them?

Many multiracial DCP feel caught in-between. First, cultural groups often base “true belonging” on ingredients like maternity or paternity, established relationships with relatives, or a traditional upbringing. This may leave us feeling like intruders or impostors within our own communities. At the same time, the world may categorize us in a way that conflicts with our internal identities or family trees. Without support to make sense of the nuances of multiracial identity, as adults, we’re left to work out together what it means to be a descendant or representative of our communities.

Multiracial DCP may feel isolated – but we build creative communities in many forms.

It’s not uncommon for multiracial DCP to feel isolated, at least before we find one another. It’s easy to see why.

First, many of us have donor sibling groups that are majority-white. ("Donor siblings" are groups of half-siblings born to families who conceived with the same donor.) Second, many online mixed-race identity spaces encourage multiracial people to find pride in their cultural upbringing or connections to genetic relatives, which many of us did not (or still don't) have access to. And third, some donors and their relatives even refuse to acknowledge that we exist. This is not just due to cultural or religious stigma about assisted reproduction, but because in some cultures and countries, close genetic relatives have a claim to inheritance or citizenship.

Online mixed-race identity spaces encourage members to find pride in their cultural upbringing or connections to genetic relatives, which many of us did not or do not have access to. Some donors and their relatives even refuse to acknowledge us not just due to cultural or religious stigma, but also because doing so could entitle the DCP to a share of inheritance or a path to citizenship in their culture or country of origin.

Given these isolating realities, we often talk about the power of seeing “someone else who looks like me,” especially genetic relatives like donors or half-siblings. However, we also find power in being seen by others like us. Before finding one another, many of us found friends and allies in fellow children of immigrants and refugees, (transracial) adoptees, BIPOC and mixed-race peers, and others who see us as we are. For us, community comes in many forms.

Despite our challenges, if there’s anything I’ve learned from our community, it’s that we build stronger identities together. Even across culture, family type, and stage of life, our stories tell us that we aren’t alone, our experiences make sense, and there’s no one right way to do life while multiracial and donor-conceived.

Looking forward: Takeaways for parents and professionals

All in all, what can the experiences of adult multiracial DCP teach us about supporting the next generations? If you’re trying to conceive (or have already become a parent) with the help of a donor of a different race, here are a few takeaways. If you’re a professional, consider incorporating these takeaways into your work.

1. Think long-term. What might your child want to know about their heritage one day? How might their level of access to relatives growing up impact their sense of belonging in heritage groups later on? Consider donors that are willing to be identified and to help your child connect to their cultural heritage.

2. Help your child connect with racial “mirrors” and cultural communities. What are your own privileges and cultural identities? Where do you live? Who is in your social circles? In the world of transracial adoption, parents are encouraged to raise their kids in communities with same-race peers and role models, or "racial mirrors," who can understand and validate their experiences. You may need to build new relationships outside your current circle, move to a more diverse area, plan trips, attend events, read books, invest in activities, and so on to help your child build a healthy identity and sense of belonging.

3. Keep seeking out education and support as your child grows up. At time of writing, I don’t know of specific resources for parents of multiracial DCP (although it's my goal to fill that gap!). In the meantime, you can tap into support communities for parents of multiracial, BIPOC, and donor-conceived children. You may especially relate to resources for parents of transracial adoptees, including ways to discuss race and identity or search for relatives. Finally, seek out stories from multiracial DCP, such as blog posts, interviews, and podcasts, and connect your child to others like them.

4. Bring up race before your child does – then keep the door open. A recent study showed that American parents wait until age 5 to start talking about race, even though kids pick up on racism starting in preschool. Donor-conceived kids’ identities and experiences will evolve as they grow up. Create an open environment for your child to talk with you about racism, othering, identity, belonging, and other nuances of their experiences. For instance, many Black families give children “the talk” about how to navigate racism, especially around authorities like police.

Max Tang is a clinical social work student (MSW ‘24) and therapist intern at Rising Hope Counseling and Wellness, a virtual therapy practice that serves LGBTQ+ and BIPOC communities in Massachusetts. She is also the Community Director of Donor Conceived Community (DCC), a US non-profit that promotes the wellbeing of donor-conceived people (DCP). At DCC, Max facilitates virtual peer support groups for multiracial and LGBTQ+ DCP; develops resources for DCP, parents, and donors; and co-leads DCC Professional Group, a learning community for family-building professionals. As a biracial Chinese American donor-conceived person, she is a passionate mental health advocate for people with intersecting identities. You can reach her at max@dccsupport.org.