Cloudy Correlation between Infertility and Cancer

Those grappling with infertility know all too well that when it rains, it pours. As if completing your family wasn’t enough to worry about, infertility adds another layer of complexity to your overall health. Several studies conducted over the past few years have linked infertility in women with an increased risk of cancer.

It’s important to note that the absolute incidence rate of cancer is still low in women of reproductive age, whether infertile or not. Facts, though, are fuel – and it’s critical that women understand all the risks associated with their infertility diagnosis and family building plan before they embark on their own unique journeys.

The Facts: Infertility is Associated with a Higher Risk of Cancer

Multiple studies across various populations suggest an association between infertility and cancer risk. A 2019 study of over 2.8 million women in Sweden found that infertility was associated with a higher incidence rate of ovarian and endometrial cancer. Ovarian cancer incidence was higher in women who had been diagnosed with endometriosis and in nulliparous women (i.e., women who never gave birth) with ovulatory issues. Endometrial cancer incidence was higher in women with ovulatory disturbances, but not in women with endometriosis.

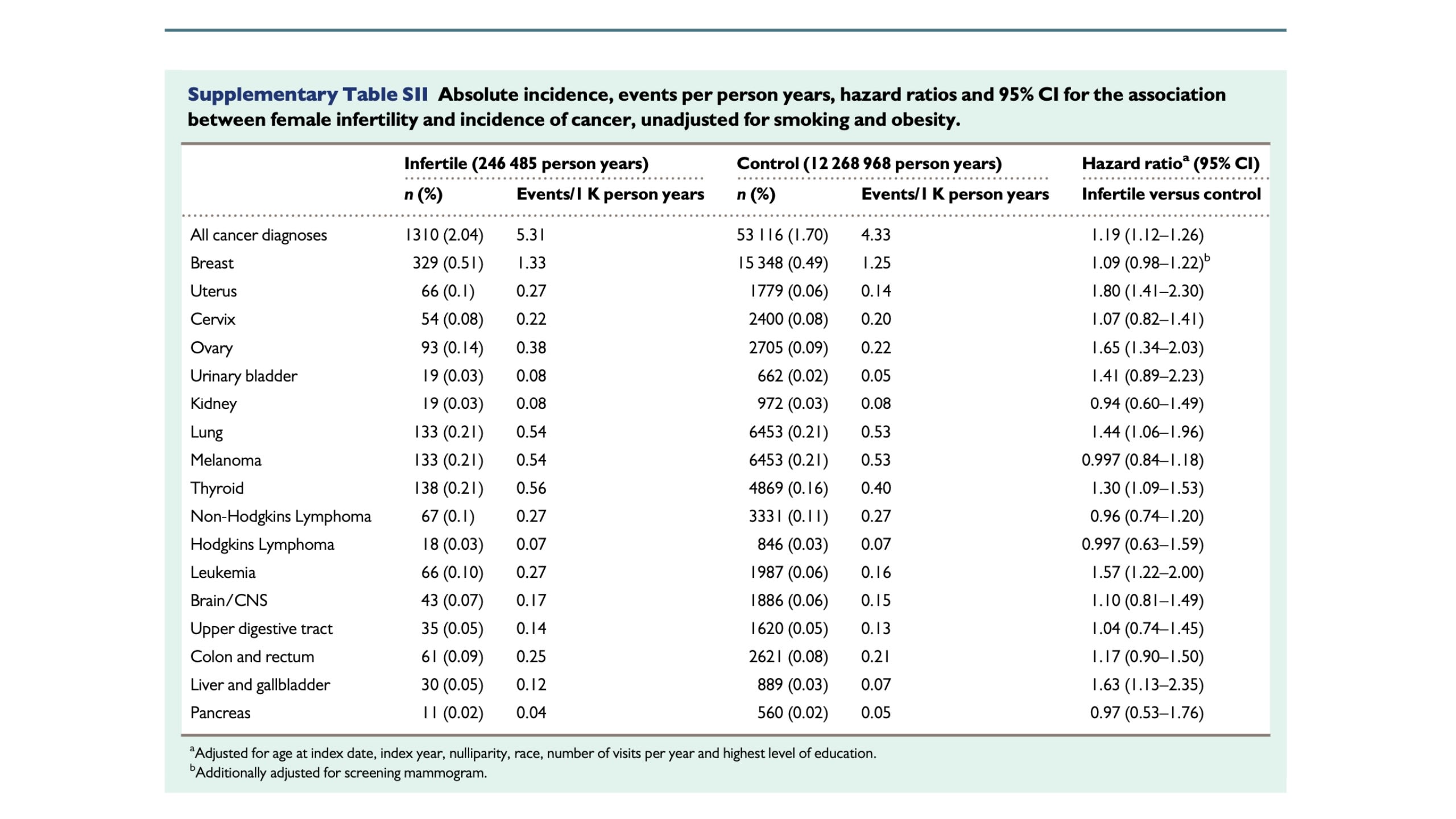

Similarly, a US-based study of over 64,000 women found a higher risk of several cancers – including uterine cancer, ovarian cancer, lung cancer, leukemia, and liver and gallbladder cancer – in infertile women. While the absolute risk of cancer was still low for both groups, the association between cancer incidence and infertility was significant; women with infertility had a 2% risk of developing these cancers, vs. a 1.7% risk for fertile women.

Risk of cancer in infertile women: analysis of US claims data

Risk of cancer in infertile women: analysis of US claims data

Just this year, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) published guidance stating that “women should be informed that there may be increased risk of invasive borderline ovarian cancers and thyroid cancers associated with fertility treatment. It is difficult to determine whether this risk is related to underlying endometriosis, female infertility, or nulliparity.”

That last sentence highlights a frustrating reality: as with so many elements of fertility, the reasons behind the challenges are, at best, murky.

A Multi-Pronged Risk Profile

Various risk factors contribute to a heightened incidence of cancer. Early onset of menstruation and late menopause are both associated with higher risks of ovarian, endometrial, and breast cancer, and pregnancy seems to impart a certain protection that decreases cancer risk. The causes of infertility are often poorly understood, and it’s hard to ascertain whether those causes could have a similarly causative effect on future cancers. As one study noted, “a recurring issue in these studies is the potential confounding by the underlying fertility. Since both causes and consequences of infertility could influence cancer risk, the relationship is complex.”

More simply stated: it’s hard to determine what, exactly, is responsible for the heightened risk of cancer among infertile women. Does the risk stem from an underlying issue – endometriosis, for example, or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) – of which infertility is merely a symptom? Or, perhaps, is the added risk due to the lack of pregnancy’s protection? Could the fertility medications infertile women use – some for months or years at a time – contribute to cancer risk? Does the true risk lie in some combination of the above?

These studies, as well as the ASRM guidelines, expound on some of these factors, while acknowledging the difficulty in attributing increased risk to any one in particular.

Risks from Underlying Fertility Issues

The studies examined herein found a correlation between cancer risk and a diagnosis of endometriosis and/or PCOS. The Norway study notes: “Sustained estrogen stimulation to the endometrium without an opposed antiestrogenic effect of progesterone, which is the usual feature of chronic anovulation and PCOS, has a recognized carcinogenic effect in the development of some endometrial cancers. The association between endometriosis and ovarian cancer is less understood and inflammatory features associated with endometriosis have been proposed as predisposing to ovarian cancer.” The US-based study conducted a subgroup analysis, which excluded women with PCOS and endometriosis. In this subgroup, the risk of uterine cancer was similar between infertile and fertile women.

The ASRM guidelines note that “endometriosis, which is present in 20%-30% of women with infertility, increases the risk of ovarian cancer nearly twofold,” and go on to cite a Danish study that concluded that women without endometriosis who received assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment did not have an increased risk of ovarian cancer, while women with endometriosis did.

It seems there may be at least a correlative relationship between underlying issues like PCOS and endometriosis and cancer. Frustratingly, it’s hard to know both the extent of that link and to understand why, exactly, it exists.

Risks from Nulliparity

In an ironic twist of fate, pregnancy seems to cast a protective halo around women vis a vis cancer risk. The US-based study conducted a subgroup analysis of women in each cohort who became pregnant and delivered a baby during the study. In this group, the risk of uterine and ovarian cancers were similar between women who had been diagnosed with infertility and those who had not.

If, as several studies have speculated, more frequent ovulation can heighten cancer risk, it might make sense that periods of reduced ovulation during pregnancy and while breastfeeding thereafter could lower that same risk.

The US-based study noted, “In patients who became pregnant and had a delivery, several risk associations that were noted in the overall comparison were diminished. Namely, the risk of developing ovarian, uterine, lung, liver and gallbladder cancer were similar between the subset of infertile and non-infertile patients who became pregnant with a subsequent delivery but were elevated in the overall comparison of infertile women to non-infertile women. As some of these cancers are hormone mediated, it does suggest a possible mechanism behind the seemingly protective effect of childbearing among infertile women who succeed in fertility treatment.”

While the exact reason for its protection is unknown – perhaps reduced ovulation, perhaps the increased progesterone and decreased estrogen levels that accompany pregnancy, perhaps something else entirely – pregnancy does seem to confer a benefit upon women regarding their cancer risk.

Risks from Fertility Medications

As the US-based study noted, “During fertility treatment, estradiol and progesterone levels are upregulated above physiologic levels…therefore, concern has also been raised regarding fertility treatment and the risk of developing hormone-sensitive cancers.” The study goes on to express a correlation between uterine cancer and clomiphene (Clomid) use.

The ASRM Guidelines delve into the theories that might explain an association between fertility drugs and ovarian cancer: “The ‘incessant ovulation’ theory suggests that prolonged and uninterrupted years of ovulation increase cancer risk. This is supported by the observations that the risk of ovarian cancer in gravid women and/or women who have used chronic ovarian suppression is decreased. Fertility drugs, which often lead to multiple ovulatory sites within the ovary during a single cycle, are, thus, hypothesized to increase the risk of ovarian cancer, whereas oral contraceptives reduce the risk by reducing the number of epithelial disruptions associated with ovulations and epithelial repair.”

It's not such a simple cause and effect, however. The Guidelines go on to explain that recent evidence has challenged the view that ovarian cancers originate primarily in the ovary, speculating that ovarian cancers often originate in other pelvic organs. This would call into question the “incessant ovulation” theory – and it weakens evidence for an association between fertility treatments and ovarian cancer.

What Does this Mean for Fertility Patients?

It’s frustrating to see questions without answers and problems without clear solutions, but it’s essential to arm yourself with as much knowledge as you can during your family building journey. The small but significant increased risk of cancer among infertile women is something all women with this diagnosis should take seriously – regardless of whether they plan to pursue ART or not.

Amid all the frustration, confusion, and confounding elements lies the opportunity inherent in scientific exploration. It’s reassuring that these associations are being studied and that scientists are pressure-testing old hypotheses and developing new ones. With each study comes the hope of more answers: a better understanding of diseases like endometriosis and PCOS for example, or improved safety regulations and patient communications for those planning to use fertility medications.

When it comes to infertility, when it rains, it pours – but sometimes, if you’re lucky, that downpour can lead to a rainbow.

Molly Donovan is a writer and content strategist who helps brands and executives develop actionable communications and content strategies and create compelling, authoritative content.

While she loves words, the best thing in her life is her daughter, for whom she and her husband are endlessly grateful to the incredible team at the Brigham and Women’s Center for Infertility and Reproductive Surgery.

You can learn more about her at mdonovancontent.com.